Reading and analyzing books by others should play an important role in your journey to writing a nonfiction book to build your personal brand as an expert in your field.

Usually, your reading takes place in your field. But, often, the best learning takes place when you read and analyze books outside of your field.

Reading outside your field removes the filters and prejudices of subject area knowledge. Since you may not recognize the titles or authors, you’re able to approach each book without preconceptions. This frees you to pay more attention to the tools and techniques the author used to engage and maintain, (or lose), your interest.

Often, the best learning takes place when you read and analyze books outside your field. This exposes you to new ideas and tips, plus mimics the way prospective readers are going to react when they pick up your published book.

What to look for when learning to write by reading

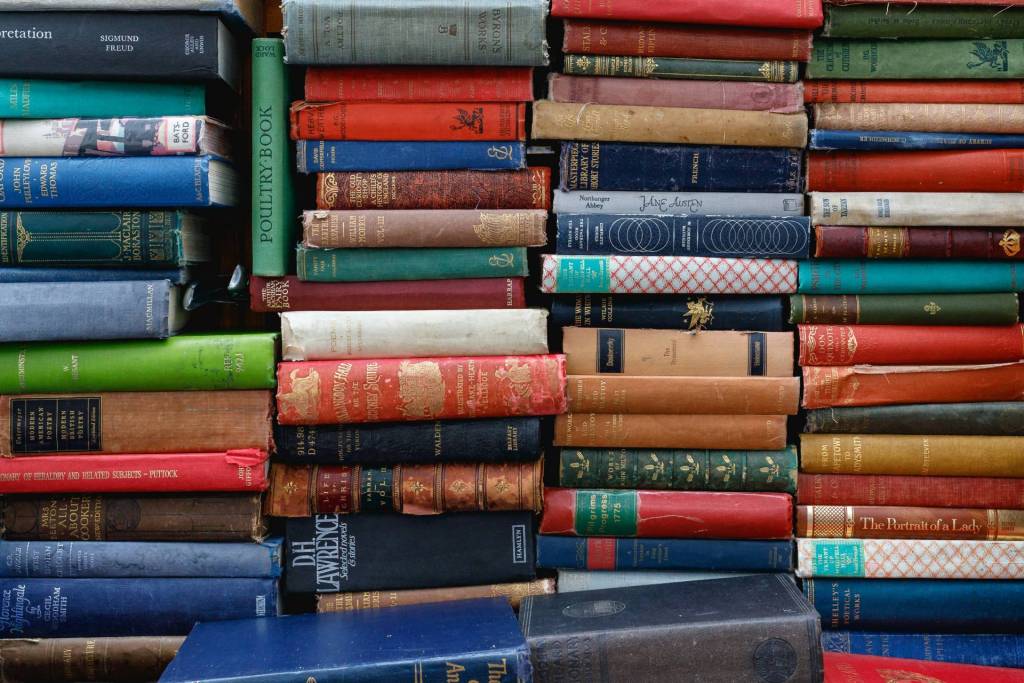

Here are 6 questions to ask yourself when exploring books outside of your field. Put these ideas to work the next time you stroll the shelves at your local Barnes & Noble or Borders bookstore, or when you visit your local public library:

- Why did you pick up the book? What attracted you to it? Were you attracted by the author’s name or the title? Was it a long title or a short title? Did the title promise a benefit for reading? Did the subtitle, or additional text on the cover, engage your interest? How long did it take you to make an “interested” or “not interested” decision? Note your reactions, because strangers picking up your book for the first time are going to react the same way you just did.

- What did you do after you picked-up the book? Did you turn the book over to see what was on the back cover? Did you open the book and start reading on a random page? Or, did you go straight to the table of contents? Do you always follow the same sequence? Again, your behavior previews the way your book will be approached by prospective readers.

- How much do you think you’ll learn from the book? How do you gauge the value of a book’s information before you read it? Are you more influenced by the author’s qualifications, pre-publication reader quotes, or the book’s table of contents. Or, do you open the book at random and skim a page or two? Many of your prospective readers will be reacting the same way.

- Does this look like an easy book to read? What is your reaction to the author’s style? How do you respond to the author’s tone? Does the author project enthusiasm and passion for sharing his knowledge, or does the author write from an impersonal, academic perspective? Did the author use frequent subheads to chunk, or visually organize, chapter content? Are visuals used to reinforce big ideas and permit easy comparisons? Did the author use assessments, exercises, and questions, to help you relate the book to your specific needs?

- Which book would I buy? Next, 3 or 4 books from the new topic your exploring to the bookstore cafe, spread them out on a table, and evaluate them from the point of view of urgency and priority. Do any of the books cry out to be taken home today? How would you rate the other books in order of importance?

- Which book offers the best value? Finally, note the selling price of each book, and re-evaluate each book’s value proposition. Which book offers the most information per dollar? Sometimes, an inexpensive introductory-level book is all that’s needed to satisfy a reader’s curiosity; in other cases, an expensive “handbook” or “guide” approach makes the best sense. What are the criteria you use to identify the best combination of information, presentation, and cost? Your prospective readers are probably going to be using the same criteria as you use to evaluate books you’re considering buying.

Create a system to learn to write by reading

Here are a couple of tips I recommend to help you create a systematic approach to learning to write by reading and analyzing books outside of your field:

- Commit to consistency. Consistency pays when writing your book and marketing your book. You’ll learn more from five 15-minute bookstore visits each week than a single 75-minute visit. Consistency reinforces the habit of constantly analyzing what others have done and looking for ways to profit from their experience and knowledge.

- Take notes as you read and compare. Create a process to track the results of your out-of-field research. It doesn’t matter whether you use yellow-pads, notecards, notebooks, or worksheets. The important thing is not to let good lessons get away! Develop a system to keep track of your observations of what works, and what doesn’t work, for others.

- Review your observations. Don’t just track your observations, get in the habit of reviewing them at consistent intervals. Perhaps, you can commit to a 30-minute review of your “observations file” the first Saturday of every month. Once again, the more you consistently perform a task, the easier it will be to develop the habit of reviewing your observations.