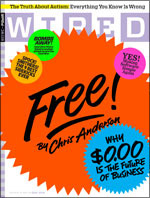

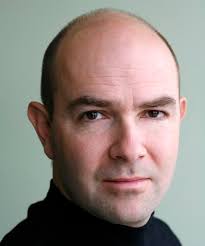

Today, I spoke to Chris Anderson, who is the editor-in-chief of Wired Magazine, as well as the New York Times bestselling author of both The Long Tail and Free: The Past and Future of a Radical Price. In this interview, Chris explains (possibly for the first time) the impact of the free economy on branding, what the best online business model is, how free impacts how products are created, and how he’s built his own personal brand through his various projects and roles.

What does the free economy mean for brands, both personal and corporate?

Let’s look at the former free that I focus on in the book which is “fremium.”

“Fremium is basically using a free form of a product as a sample to drive demand for a paid one; where the majority of people get the free form and the minority converts to paid. In this case, the free form of the product substitutes for traditional advertising.

To some extent, the actual product becomes the primary vehicle of marketing, rather than the brand or the advertisement. You know, great products market themselves. They market themselves because of their utility; because you’re not telling somebody about it. Instead, you’re letting them experience it. They do the marketing based on how useful they are to people.

The classic definition of brand, and my understanding of brand, is that:

“Brands are a proxy for missing information in a world where consumers don’t have exact information.”

They use brands to substitute; they use brands to stand in for information they are missing about things like quality. So, you know, if you aren’t an expert on mp3 players, buying an Apple iPod is a safe bet because the name Apple and the brand iPod stands for a certain degree of quality. You don’t have to become an expert to make a good choice. Um, if however all these products were available for free, and you were able to sample them and try them with no risk associated, then you would go for the product that offers the most utility to you- and you wouldn’t have to settle on the brand to tell you which way to go.

So, in a sense, free products level the information playing field – they give consumers information that allows them to make wise choices that allows them to depend on brands somewhat less. In other words: free products speak for themselves. Now does that mean that a brand doesn’t matter? Absolutely not. Brands still matter, but you could argue that in a world where people could sample products rather than just having to hear about them, the brand doesn’t matter as much as it did in the traditional world where you use brands to reduce your risks of disappointment.

What do you think the best online business model is in the free economy? Freemium as you say. Maybe explain that a little bit more?

Yeah, so I think. Free is perhaps the most misunderstood four-letter word beginning with F in the English language. Among the many misunderstandings about free are some misunderstandings about the book; which is that some people think that in our marketing, everything should be free. Or that everything should be advertising supportive. In fact, the book certainly acknowledges the ad-model, but focuses more on freemium- which is the combination of free and premium.

The best way to think about that is a version of the traditional free sample: as your selling muffins, you might give out one percent of your muffins as free samples to sell the rest. You can’t really give out much more than that or you will go bankrupt because there are real costs associated with those muffins. The freemium model, which really only works in the digital space and, you know, additional markets, is one where you give out 80 percent or 90 percent of your product in a free form to drive demand for a superior paid version that maybe ten percent of the people want. And because digital products are so cheap and getting cheaper, that ten percent paying users can subsidize 90 percent free users and everybody wins.

They use free as a form of marketing to reach the maximum possible audience, and then offer two products – a free version and a paid version with the hope that the most engaged consumers and that the most active power-users will see the value in the product, will use the product and love the product – see the value in the product such as they want additional feature that they be willing to pay for that.

Will free force businesses and people to work harder, fast, smarter and deliver higher quality products?

“Free is defined as freemium-based business models online.”

Free is where the products market themselves; where the free form of the product is the advertisement. What that requires is that you can’t just tell people about the products or, you know, come up with the ad campaign.

The products actually need to:

- A: be useful

- B: be so useful that some people are willing to pay for more

So the product has to be great. Free is not a silver bullet that makes every product marketable. Free is a great way to allow people to sample the products, but if they don’t like what they are sampling, or if they are not thrilled or delighted and wanting more, then you know, you can’t convert them to paid. So, you know, it’s never been a good idea to have a bad product, but now when you are in the freemium model, having a product is not a sufficiently compelling guarantee that the freemium product will work for you because the sampling tells people all they need to know – which is that the product is not worth paying for.

Can you give an example of a company that has used the free model before competitors and has succeeded?

You know it’s been interesting to watch even companies like Intuit that use free. Intuit sells Turbo Tax and you know, Turbo Tax was and probably still is a box you can buy in the store. But it’s also an online service and what they chose to do was to make Turbo Tax online free in one form, which is your federal tax, and then if you wanted to do your state taxes, well, that would be paid. Now, I don’t know of anybody who did this before them. But it was clearly possible for someone to do this. It is just software. When you offer software online the marginal costs are so close to zero that free becomes a possibility. I don’t know of anybody else who made, at least not this level of quality, made federal tax filings free.

Now, I have a hard time answering this question precise because I don’t know the details of every particular. The way you phrased the question is somebody coming into it before the competitors. I can’t guarantee that there wasn’t another tax preparation software package out there for free. But, I don’t think it was anything on this scale, and it is interesting that Intuit, in a sense, cannibalized their own business and took one of their own products and made it free because they recognized that if they didn’t, somebody else would. It is also very interesting how they made their free premium divide. Federal free. State paid. We Americans all live both in this country and a state. So, you know, I suspect their conversion rate is really quite high. If you have already entered all your information into the federal one, it’s very compelling to upgrade to state.

How have you built your personal brand both at Wired Magazine and as an author? Is it challenging to balance both, and how do they support each other?

It just so happens that all of my projects kind of overlap – they are complimentary. I think my last book, The Long Tail, started as a series. I give speeches a lot. That’s what the editors are required to do and are expected to do and it is a good thing for our public profile for editor to be out there. Now, when I give a speech, I need to have something to say. So I end up doing a lot of research to create speeches and have something unique and fresh to say. And in the course of doing that research, I eventually stumbled back in ‘94 on some data that was so interesting and surprising that it led to a series of speeches on (what became The Long Tail). So my public presence as part of my job led to my research, and the research led to an epiphany, and epiphany that led to more research, which led to an article in Wired, which then led to more feedback, which revealed more data, which then led to the decision to write a book. I wrote a book which we then ran an exc erpt in Wired. It was published, and I gave more speeches about it. You know, I am known as the author of The Long Tail, but also the editor of Wired because The Long Tail originated in Wired. The two are seen as very complimentary.

erpt in Wired. It was published, and I gave more speeches about it. You know, I am known as the author of The Long Tail, but also the editor of Wired because The Long Tail originated in Wired. The two are seen as very complimentary.

Free was the same model, although at this point free emerged from The Long Tail research rather than substantial known work. Once again, it is a good thing for the editor of Wired to have a public presence. It is a good thing to have public presence to be about the subject matter that Wired covers. It is a good thing if you are in the thought-leadership business, which is kind of a terrible term that I use with caution.

Ideas, and packaging ideas is what we do here at Wired. You know, ideally these ideas are fresh and powerful and we package them in different ways. We package them with words and pictures in design in the magazine. We package them in speeches. We package them in books. But it is all about packaging ideas that resonate. The magazine is one way to do it. Books are another way to do it. Speeches are another way to do it – but it is all about idea propagation. These ideas are all coming from the same place – which is how technology is changing the world. They all seem to complement each other. So there is kind of the logic between all my various personas. They all come from the same place, which is how technology is changing the world and ways to understand that that we can all use.

—- —–

—–

Chris Anderson is the editor-in-chief of Wired Magazine, and is one of the most knowledgeable, insightful and articulate voices at the center of the new economy. He consistently understands before anyone else the new directions the economy is taking and then names the central phenomenon, giving us handles for the business opportunities they represent. With his New York Times bestseller The Long Tail, he named the rise of the niche as a powerful new force in our economy—why the future of business is selling small quantities of more things to the few people who want those things; how all of those small communities together make up a vast market potential, and how the efficiencies of digital and web technology make it possible. Now Chris has published the New York Times bestseller Free: The Past and Future of a Radical Price, originally as an article in Wired magazine. He worked at The Economist for seven years in various positions and served as an editor at the two premier science journals, Science and Nature. Education background in physics, including research at Los Alamos.